At Liberty is a weekly podcast that explores the most pressing civil rights and civil liberties questions of our time. Catch new episodes on Thursday at 9am ET.

episodes

December 14, 2023

2023 in Review: The Latest on the Stories That Made Our Year

2023 is coming to a close, and we have weathered so much this year. At the ACLU, we continue to fight for civil rights and civil liberties across the country. We’re prying open every opportunity for abortion access and reproductive health care following the overturn of Roe, blocking trans health...

2023 is coming to a close, and we have weathered so much this year. At the ACLU, we continue to fight for civil rights and civil liberties across the country. We’re prying open every opportunity...

October 12, 2023

We're Suing Florida for Anti-Asian Housing Discrimination

This May, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed SB 264, a law that restricts Chinese nationals from acquiring property in the state of Florida under the guise of protecting national security. But the issue is actually pretty clear — Chinese people are not the Chinese government, and conflating the two is just...

This May, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed SB 264, a law that restricts Chinese nationals from acquiring property in the state of Florida under the guise of protecting national security. But the issue is actually pretty...

May 11, 2023

Banning TikTok is a Really Bad Idea

The social media platform TikTok has had a meteoric rise. The app has become a hub for educators, activists, and creatives to influence all aspects of culture. From launching dance trends, catapulting decades old books onto best sellers lists, to educating voters and organizing changemakers, TikTok has become key to how...

The social media platform TikTok has had a meteoric rise. The app has become a hub for educators, activists, and creatives to influence all aspects of culture. From launching dance trends, catapulting decades old books...

October 6, 2022

Is the Government Tracking Your Abortion?

If you live in a state where abortions have been banned since the overturn of Roe v. Wade, accessing abortion is a huge challenge. But unfortunately, access is not the only challenge -- pursuing an abortion without leaving a trace poses another huge hurdle. If you search for resources online,...

If you live in a state where abortions have been banned since the overturn of Roe v. Wade, accessing abortion is a huge challenge. But unfortunately, access is not the only challenge -- pursuing an...

November 4, 2021

Can the Government Wrongfully Spy on You and Get Away With It?

This week, we are bringing you a story about an upcoming Supreme Court case: FBI v. Fazaga, set to be argued on November 8th. This case will have big implications on the ability for private citizens who have been wrongfully surveilled by the U.S. government to seek redress for the...

This week, we are bringing you a story about an upcoming Supreme Court case: FBI v. Fazaga, set to be argued on November 8th. This case will have big implications on the ability for private...

September 9, 2021

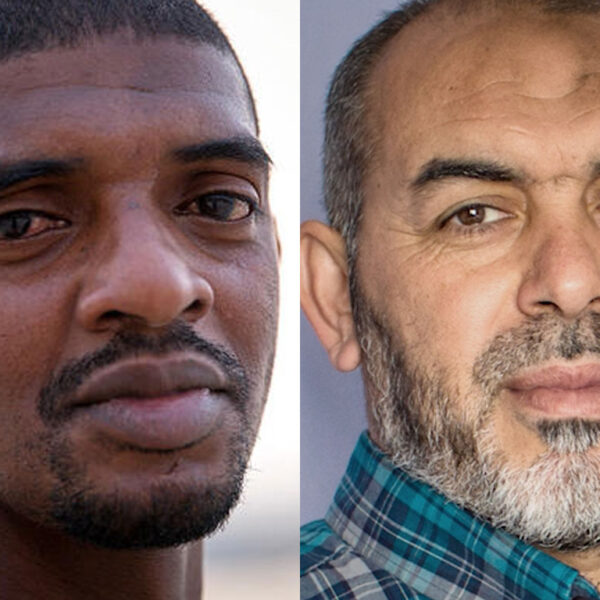

Survivors of the CIA Torture Program Almost 20 Years Later

As we approach the 20-year mark since September 11th, we are following up with the clients and the attorney of one seminal ACLU lawsuit on the CIA’s post-9/11 torture program, a program that ended in 2010 but that continues to haunt its survivors and to stain the U.S.’s international human...

As we approach the 20-year mark since September 11th, we are following up with the clients and the attorney of one seminal ACLU lawsuit on the CIA’s post-9/11 torture program, a program that ended in...

April 1, 2021

Why New Domestic Terrorism Laws Won't End White Supremacy

From a Capitol insurrection to multiple mass shootings, recent violence is prompting an old debate: Does the U.S. need a domestic terrorism law? And if not, how do we quell this violence? Our guest today, Hina Shamsi, the Director of the National Security Project at the ACLU, says we don’t...

From a Capitol insurrection to multiple mass shootings, recent violence is prompting an old debate: Does the U.S. need a domestic terrorism law? And if not, how do we quell this violence? Our guest today,...

August 6, 2020

The Constitutional Crisis Wrought by Trump's Federal Troops

In the last month, we’ve seen the Trump administration deploy federal law enforcement officers to Portland, Oregon. Those agents have been documented using sharpshooters to maim protesters, sweeping people away in unmarked cars, and attacking journalists, legal observers, and medics with tear gas. The federal government just agreed to withdraw...

In the last month, we’ve seen the Trump administration deploy federal law enforcement officers to Portland, Oregon. Those agents have been documented using sharpshooters to maim protesters, sweeping people away in unmarked cars, and attacking...

October 1, 2019

Edward Snowden's Permanent Record

In his new memoir, "Permanent Record," Edward Snowden tells the story of his evolution: A child of civil servants, he fell hard and fast for the internet of the 90s, ascended the intelligence community, and became one of the most famous whistleblowers in U.S. history. He joins ACLU Executive Director...

In his new memoir, "Permanent Record," Edward Snowden tells the story of his evolution: A child of civil servants, he fell hard and fast for the internet of the 90s, ascended the intelligence community, and...

September 11, 2019

How the War on Terror Corrupted America

Eighteen years after the attacks of September 11, 2001, a trial date was recently set for the men accused of plotting those attacks. But what has taken so long? And is a fair trial even possible? On this anniversary of 9/11, we're replaying an interview from last year with Hina...

Eighteen years after the attacks of September 11, 2001, a trial date was recently set for the men accused of plotting those attacks. But what has taken so long? And is a fair trial even...